Introduction

Brief Overview of India-China Relations

One of the most important and intricate relationships in contemporary geopolitics is that between China and India. China and India, two of the world’s most populous countries and two of the oldest civilizations, have a lengthy and changing history together. The relationship between China and India gained political significance in the middle of the 20th century, with China following the communist revolution in 1949 and India following its independence in 1947.

Since then, the relationship between China and India has gone through a number of stages, including war, tension, friendship, and cautious cooperation. Despite historical differences, the relationship between China and India continues to influence global geopolitics, Asian stability, and regional peace, reflecting both countries’ increasing power in the twenty-first century.

Historical Background Before 1947 (Civilizational and Trade Ties)

Deep civilizational, cultural, and commercial ties underpinned the India-China relationship long before contemporary nation-states emerged. Silk, spices, and valuable ideas were all traded along the ancient Silk Road, which connected China and India. Monks like Fa-Hien, Hiuen Tsang (Xuanzang), and I-Tsing traveled from China to India to study Buddhist texts and brought them back to India to promote cultural harmony. Buddhism was instrumental in deepening India-China relations. Mutual respect for literature, art, and philosophy characterized ancient India-China relations, which promoted harmony and spiritual development. One of the oldest and most significant relationships in Asian history was established by the India-China bond, which was based on shared values and cultural enrichment.

Importance of India-China Relations in the Asian and Global Context

The India-China partnership represents nearly one-third of the world’s population and stands as a driving force behind global economic growth. As two of the fastest-growing economies, the India-China dynamic directly impacts Asia’s political, economic, and strategic balance.

Regional Impact: The India-China presence shapes the balance of power in South Asia and East Asia, influencing major regional organizations like BRICS, SCO, and ASEAN.

Global Impact: On international issues such as climate change, trade, and global governance, India-China cooperation and dialogue carry tremendous global significance.

Strategic Importance: As nuclear powers and influential members of the United Nations, India-China relations determine global peace, stability of supply chains, and the evolution of a multipolar world order.

In essence, the India-China relationship is far more than a connection between two neighbors — it symbolizes the direction of Asian leadership and the foundation of a new global order.

Early Phase (1947–1959): Friendship and Idealism

After gaining independence in 1947, India sought peaceful and cooperative relations with its neighbors – and China was central to that vision. This phase is often remembered as a period of idealism, mutual admiration, and hope for Asian solidarity.

a) Recognition and Diplomatic Relations (1950)

When the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was established under Mao Zedong in 1949, most Western countries were hesitant to recognize the new communist government. However, India took a bold diplomatic step by becoming one of the first non-communist countries to officially recognize the PRC in 1950, marking the beginning of India–China relations. This early phase of India-China relations reflects India’s foreign policy of non-alignment and goodwill towards its Asian neighbour. Furthermore, India supported China’s right to represent itself in the United Nations by removing Taiwan’s seat – an important gesture that deepened initial diplomatic trust and strengthened the foundation of India-China cooperation in global affairs.

India’s Early Recognition of the People’s Republic of China

India’s initial recognition of communist China was guided by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s idealistic vision of Asian unity and anti-colonial solidarity. Nehru believed that India and China – the two great Asian civilizations – were natural partners in the reconstruction of Asia after centuries of Western dominance. This trust became the cornerstone of India-China relations, fostering mutual respect and cooperation. Diplomatic recognition not only strengthened political ties but also laid the foundation for early cooperation between India and China in culture, trade and international forums, opening a new chapter in India-China friendship and regional partnership.

b) “Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai” Era

During the 1950s, the famous slogan “Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai” (Indians and Chinese are brothers) became a powerful symbol of India-China friendship and growing diplomatic warmth. This period marked a golden phase in India-China relations, as both governments emphasized Asian solidarity, peace and mutual respect. The India–China partnership was portrayed as a model of post-colonial cooperation and unity in newly independent Asia. Public enthusiasm, cultural exchanges and extensive media coverage further strengthened the image of India-China unity, promoting a shared vision of peace, progress and a common Asian destiny.

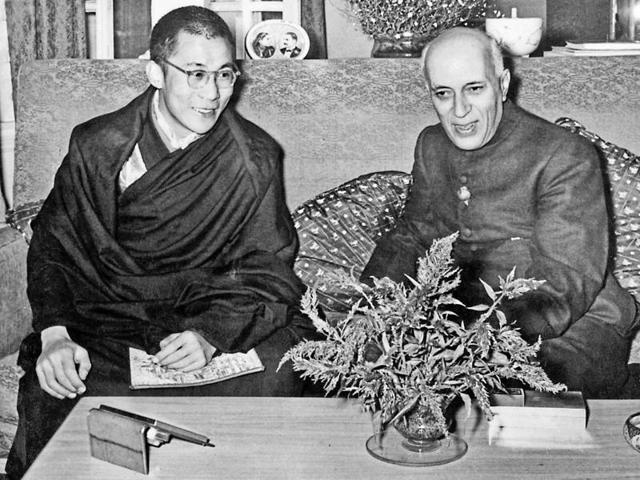

Cultural Exchanges and Nehru–Zhou Enlai Diplomacy

There were frequent high-level visits between Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai. Cultural delegations, student exchanges and friendship societies were formed to deepen people-to-people contacts. The two leaders emphasized the need for non-alignment, anti-imperialism and peaceful co-existence, reflecting the values they shared at that time. However, whereas Nehru emphasized moral diplomacy, Zhou Enlai took a more pragmatic approach – a difference that would later lead to misunderstandings.

c) Panchsheel Agreement (1954)

One of the most important achievements of this period was the signing of the Panchsheel Agreement (Agreement on Trade and Contact between China and the Tibet Region of India) in 1954.

It introduced the five principles (Panchsheel) of peaceful coexistence:

- Mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty

- Mutual non-aggression

- Non-interference in each other’s internal affairs

- Equality and mutual benefit

- Peaceful coexistence

The Panchsheel Agreement was seen as a symbol of idealistic diplomacy – aimed at building trust and cooperation between the two emerging Asian powers.

Principles of Peaceful Coexistence

These five principles were not only at the core of India-China relations, but also became the moral foundation of India’s foreign policy and China’s diplomatic strategy with other countries.

He emphasized peaceful resolution of conflicts and respect for sovereignty – an alternative to Western power politics.

However, ironically, subsequent border conflicts would test the strength of these same principles.

d) Tibet Issue (1950–59)

Tibet became the first major point of tension between India and China. In 1950, China annexed Tibet, which historically served as a buffer zone between the two countries.

India accepted China’s sovereignty over Tibet in 1954, hoping this would lead to peace and mutual respect. However, this led to uncertainty over the undefined Himalayan border, as the traditional boundaries were never clearly demarcated.

India’s Acceptance of Chinese Sovereignty Over Tibet

India formally recognized Tibet as part of China in the Panchsheel Agreement (1954). Nehru believed that supporting China’s territorial claim would ensure stability and friendship.

However, this decision weakened India’s strategic buffer and later allowed China to build infrastructure, such as the Aksai Chin road, across disputed areas — creating long-term border friction.

Refuge of the Dalai Lama and Rising Tensions (1959)

In 1959, the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s spiritual leader, fled to India after a failed rebellion against Chinese control. India gave him political asylum, which made China very angry.

This incident proved to be a turning point – China began to view India with suspicion and accused it of interfering in internal affairs.

Tension over Tibet, coupled with unresolved border issues, ultimately led to a breakdown of trust and led to the India-China War of 1962.

Conflict and Estrangement (1959–1976)

This phase marked a sharp decline in India–China relations, shifting from friendship to hostility. The idealism of the 1950s gave way to mistrust, military conflict, and diplomatic isolation. The key reasons were border disputes, the Tibet issue, and China’s growing ties with Pakistan.

a) Border Disputes (Aksai Chin and NEFA/Arunachal Pradesh)

The India-China border, more than 3,400 kilometers long, was never clearly defined under British rule. When both nations became independent, they inherited unclear borders, leading to competing territorial claims.

Western Area (Aksai Chin): China claims the Aksai Chin region in Ladakh as part of its Xinjiang province. However, India considered it a part of Jammu and Kashmir. China built a road through Aksai Chin in the 1950s to link Xinjiang and Tibet – this angered India, as it was seen as a violation of sovereignty.

Eastern Region (NEFA/Arunachal Pradesh): China rejected the McMahon Line (1914) as an imperial boundary and claimed parts of the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA, now Arunachal Pradesh). However, India considered the McMahon Line as its legitimate border. These two disputed areas became the main cause of the 1962 war.

b) Sino-Indian War of 1962

The rising tensions escalated into a full-scale war in October 1962 when Chinese forces crossed into both Aksai Chin and NEFA.

Reason:

- Border disputes – competing territorial claims in Aksai Chin and NEFA.

- India’s Forward Policy – India began establishing small military posts in disputed areas to establish control.

- Chinese suspicion after the Dalai Lama’s asylum (1959) – China viewed India as supporting Tibetan separatism.

- Mutual distrust and lack of communication – diplomatic efforts to resolve disputes failed.

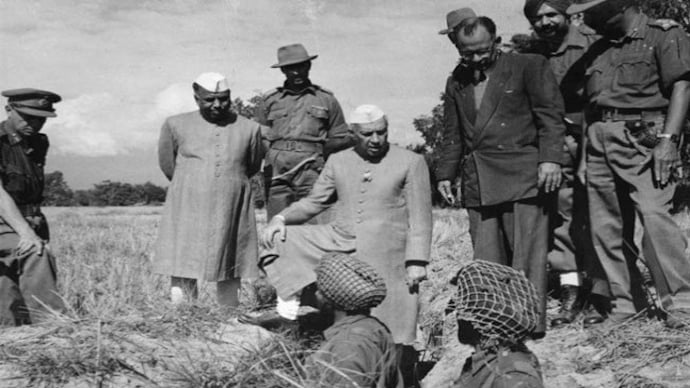

Events:

- In October 1962, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) launched coordinated attacks in both areas.

- The Chinese army advanced rapidly and captured key posts in Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh.

- Indian troops were ill-prepared, inadequately equipped and suffered heavy losses.

- The war lasted only for about a month.

- China declared a unilateral armistice on 21 November 1962, withdrawing from NEFA but retaining control over Aksai Chin.

consequences:

- Humiliating military defeat for India and loss of confidence in China.

- The collapse of Nehru’s idealistic foreign policy, which was based on peace and Asian solidarity.

- There was a major shift in India’s defense policy towards modernization and preparedness.

- Bilateral relations entered a period of long-term distrust and bitterness.

c) Post-War Relations

Diplomatic relations between India and China were badly damaged after the 1962 war.

Both countries withdrew ambassadors; Only low-level diplomatic contacts remained. Cross-border communication and trade through traditional routes such as Nathu La and Jelep La were stopped. The border remained militarized and heavily patrolled, creating psychological and political divisions. This period (1962–1976) is often referred to as “stagnation” in India–China relations.

d) Border Standstill and Diplomatic Freeze

For more than a decade after the war, both nations avoided direct engagement.

- No significant diplomatic or political dialogue occurred.

- Skirmishes like the Nathu La clash (1967) in Sikkim reinforced hostility.

- China’s domestic focus was on the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), while India was dealing with internal political and economic challenges.

This “cold silence” reflected a complete breakdown of trust and cooperation.

e) Impact on India’s Foreign and Defense Policies

The 1962 defeat was a turning point in India’s national security outlook.

- Defense Modernization: India restructured its armed forces, improved mountain warfare capability, and increased defense spending.

- Foreign Policy Shift:

- India moved from idealistic non-alignment to pragmatic realism.

- It sought closer ties with the Soviet Union, which became India’s key defense partner.

- Self-Reliance: India focused on developing indigenous arms production and defense industries.

- Public Perception: The emotional blow of 1962 left a deep mistrust of China in Indian public opinion for decades.

f) China’s Relations with Pakistan and Support in the 1965 and 1971 Wars

After the war with India, China strategically aligned with Pakistan, India’s rival, to counterbalance Indian influence in South Asia.

- 1963: Pakistan and China signed a border agreement, where Pakistan ceded parts of PoK (Shaksgam Valley) to China — strengthening their partnership.

- During the Indo-Pak War of 1965, China issued warnings to India, indirectly supporting Pakistan.

- In the 1971 Indo-Pak War, which led to the creation of Bangladesh, China again supported Pakistan diplomatically and opposed India’s intervention.

This China–Pakistan alliance became a permanent feature of South Asian geopolitics, further complicating India–China relations.

Normalization and Rapprochement (1976–1990s)

After nearly 15 years of silence and hostility following the 1962 war, India and China gradually began to rebuild their relations. This phase marked the gradual normalization of diplomatic relations, cautious negotiations on border issues, and the revival of cultural and economic contacts.

a) Restoration of diplomatic relations (1976)

In 1976, India and China restored full diplomatic relations by exchanging ambassadors again for the first time since 1962.

This step marks the beginning of a softening in the relationship.

The global context had also changed – both nations were facing internal challenges and external pressures: China had emerged from the Cultural Revolution and wanted to reconnect with the world.

India was recovering from the Emergency period (1975–77) and wanted stability in foreign policy.

This re-establishment of diplomatic channels laid the groundwork for dialogue and confidence-building.

b) High-level visits (Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Rajiv Gandhi)

Diplomatic normalization was followed by political visits that symbolized reconciliation:

- 1979: Indian Foreign Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee visited China – the first high-level Indian visit since 1960. Although his travels were cut short due to China’s invasion of Vietnam, it marked the beginning of renewed communication.

- 1988: Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s historic visit to Beijing further transformed relations. He met with Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping and both sides agreed to temporarily set aside the border dispute and focus on other areas of cooperation.

Rajiv Gandhi’s visit is often considered a turning point in post-war India–China relations.

c) Confidence-Building Measures (CBM) at the Borders.

To prevent another military confrontation, both countries agreed to create mechanisms to maintain peace on the border:

- Establishment of Joint Working Groups (JWG) to discuss the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

- Agreements to avoid armed conflict and improve border communications.

- Regular meetings between defense and foreign officials.

These CBMs helped in reducing tension on the border and created a sense of predictability in the disputed areas.

d) shift towards pragmatic diplomacy

In contrast to the idealism of the 1950s, this period saw both realistic and pragmatic approaches:

- Both countries felt that cooperation was mutually beneficial and that conflict hindered economic development.

- Under Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, China adopted an “open door policy” in seeking trade and investment partners.

- India, facing economic and political challenges, recognized the importance of stable relations with key neighbours.

This pragmatic approach replaced ideological rivalry with issue-based diplomacy.

e) Trade and Cultural Exchanges Resume

As tensions reduced, trade and cultural links began to recover:

- In 1978, limited border trade was reopened through passes like Shipki La and Nathu La.

- Cultural delegations, art exhibitions, and academic exchanges resumed.

- Direct flights and tourism began to reconnect people-to-people ties.

By the late 1980s, bilateral trade and cultural cooperation became key instruments of soft diplomacy.

Post-Reform Era (1990s–2000s): Economic and Strategic Engagement

The period from the early 1990s to the early 2000s was a major turning point in India–China relations. The two countries began to view each other not only as rivals, but as potential partners in trade, investment and regional cooperation.

China’s economic rise under Deng Xiaoping’s reforms and India’s liberalization in 1991 created new opportunities for engagement while managing deep mistrust.

a) economic cooperation

During this period, both India and China recognized that economic interdependence could serve as a stabilizing factor in their relations.

Trade boom: Bilateral trade, which was only a few hundred million dollars in the early 1990s, grew to more than $20 billion by the mid-2000s.

China became one of India’s largest trading partners, exporting machinery, electronics and chemicals, while importing Indian raw materials, iron ore and textiles.

Both countries participated in regional economic forums and initiated discussions on cooperation in infrastructure, science and technology. However, the growing trade imbalance (China is exporting far more than it imports) started to worry Indian policy makers, setting the stage for future economic friction.

b) India’s Look East Policy

India launched its Look East policy in the early 1990s to strengthen ties with Southeast Asian countries and balance China’s growing influence in Asia.

- India aims to integrate economically with ASEAN countries through trade and connectivity projects.

- This indirectly led to a healthy competition between India and China for influence in Asia.

- While China expanded its Belt and Road-style initiative, India promoted connectivity and democratic cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region.

This policy gave India a broad strategic vision and established it as a rising Asian power along with China.

c) political engagement

Diplomatic dialogue expanded through regular high-level visits and border meetings:

- The Joint Working Group (JWG) on border issues, established in 1988, continued active discussions until the 1990s.

- President K.R. Visits by leaders such as Narayanan (2000) and Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee (2003) reflected growing mutual trust.

- In 2003, both countries appointed special representatives to negotiate more effectively on border disputes – a sign of institutionalized dialogue.

This phase reflected maturity in diplomacy, as both sides agreed to separate their economic cooperation from the border issue.

d) Agreements on Peace and Tranquility (1993, 1996)

Two historic agreements were signed to maintain peace along the Line of Actual Control (LAC):

1.1993 Agreement on maintaining peace and stability on LAC

- Both sides agreed to respect the LAC, reduce troop levels and avoid military escalation.

2. 1996 Agreement on Confidence-Building Measures (CBM)

- Practical measures such as prior notice of military exercises, ban on use of firearms near the border and transparency in army activities were introduced.

These agreements helped prevent large-scale conflict and were instrumental in maintaining relative peace for more than a decade.

e) Regional and global forums (BRICS, SCO, climate talks)

By the 2000s, India and China began to cooperate in multilateral fora to promote shared global interests:

- BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa): The two countries worked together on reforming global financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank.

- Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO): India engages with China on regional security and counter-terrorism.

- Climate change talks: The two countries coordinated positions in global climate talks, emphasizing “common but differentiated responsibilities” for developing countries.

Such collaboration enhanced their image as a voice for the Global South and demonstrated that their partnership extended beyond bilateral issues.

The Border Issue: Persistent Disputes

Despite decades of talks and agreements, the India–China border dispute remains unresolved. It continues to be the most sensitive and complex aspect of their relationship — shaping their diplomacy, defense strategy, and mutual trust.

a) LAC (Line of Actual Control) — Undefined Boundaries

The Line of Actual Control (LAC) represents the de facto border between India and China.

However, unlike a formally agreed boundary, the LAC is not clearly demarcated or mutually recognized.

- India and China have different perceptions of where the LAC lies — leading to overlapping patrol zones and face-offs.

- The LAC spans three sectors:

- Western Sector – Ladakh (Aksai Chin area)

- Middle Sector – Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand

- Eastern Sector – Arunachal Pradesh (claimed by China as “South Tibet”)

The lack of a clear boundary has made the region prone to recurrent standoffs and military tensions.

b) Major Standoffs and Clashes

Even after the 1993 and 1996 peace agreements, periodic confrontations have taken place along the LAC. The key incidents include:

1. Sumdorong Chu Incident (1987):

A minor military standoff in Arunachal Pradesh after Chinese troops intruded into the Sumdorong Chu Valley.

Although tensions were defused diplomatically, it exposed the fragile nature of the peace.

2. Doklam Standoff (2017):

Located near the tri-junction of India, Bhutan, and China, Doklam became the site of a 73-day military face-off between Indian and Chinese forces.

- China’s attempt to construct a road in Bhutanese territory was opposed by India due to its proximity to the Siliguri Corridor (India’s ‘Chicken’s Neck’).

- The standoff ended through diplomatic dialogue, but it showed that strategic mistrust persisted.

3. Galwan Valley Clash (2020):

The most violent border clash in over four decades occurred in Ladakh’s Galwan Valley.

- It resulted in the deaths of 20 Indian soldiers and several Chinese troops.

- The clash shattered decades of peace and led to a massive military buildup along the LAC.

- It froze bilateral ties once again and triggered economic and technological restrictions by India against Chinese firms and apps.

c) Impact on Trust and Military Relations

These repeated border tensions have deeply affected mutual confidence:

- Military Build-Up: Both sides have heavily militarized the border regions, building new roads, airstrips, and logistics hubs.

- Breakdown of Communication: Despite several rounds of military and diplomatic talks, disengagement has been slow and partial.

- Erosion of Trust: The Galwan incident especially ended the fragile peace built since the 1990s, reviving suspicion and nationalism on both sides.

- Public Perception: In India, public opinion turned sharply negative toward China, leading to calls for boycotts and stricter security measures.

d) Diplomatic and Negotiation Efforts

To manage these recurring crises, both countries have continued dialogue through:

- Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination (WMCC) on border affairs.

- Special Representatives’ Talks on the boundary question (launched in 2003).

- Military-level talks after Galwan to achieve phased disengagement.

However, progress remains slow, as both sides are unwilling to compromise on territorial claims. The border dispute has thus become a long-term strategic challenge, affecting every aspect of bilateral relations.

Conclusion: India–China Relationship After Independence

The journey of India-China relations since 1947 has been a story of hope, struggle and cautious cooperation. Emerging from shared struggles against colonialism, both countries began the post-independence era with idealism and mutual respect – epitomizing the spirit of “Hindi-Chinese Bhai Bhai”. However, this optimism quickly faded after the 1962 war, which left behind deep scars of mistrust and strategic rivalry.

Over the decades, both countries have attempted to rebuild relations through diplomacy, trade and confidence-building measures. The normalization of relations since the late 1970s, growing economic participation in the 1990s and 2000s, and their cooperation in global platforms such as BRICS and SCO have shown that coexistence and interaction are possible. Nevertheless, relations remain fragile and complex, dominated by border disputes, strategic competition and geopolitical suspicions. Incidents like Doklam (2017) and Galwan (2020) have shown how easily tensions can ruin years of diplomatic progress.

In today’s world, India and China are not just neighbors – they are civilizational powers shaping the destiny of Asia. Their actions affect regional security, global trade, and the balance of power in the 21st century. For lasting peace and prosperity, both must adopt a realistic but cooperative approach – managing competition without conflict and building trust through sustained dialogue. Ultimately, the future of India-China relations will depend on mutual respect, strategic patience and a shared vision for Asia that will be defined not by rivalry, but by partnership and peaceful coexistence.

Also Read : https://oasisstudy.space/india-us-relation-a-brief-exploration/

Leave a Reply